Me, my family & other resources is a CLARIN:EL initiative which aims to present a selected resource from the CLARIN:EL Central Inventory on a monthly basis. In addition, other CLARIN:EL resources considered to be distant or close relatives of the featured resource are also presented, as members of a family with a common name.

These families are organized according to certain common features of the resources (e.g. domain and/or thematic area, resource type, media type, time period/coverage, etc.). They are similar to human families, whose members may live independently in different parts of the world, however, they constitute a unified whole where each member retains its autonomy and particular characteristics.

So, where were these resources born and how did they get into CLARIN:EL? Which family do they belong to? Are there any other members of the same family in the CLARIN:EL Infrastructure or in the CLARIN ERIC European Infrastructure?

Stay tuned and discover each month a different resource, its family, as well as its close, or maybe not so close, relatives!

From the beginning of the 20th century to CLARIN:EL

On the occasion of the International Greek Language Day (9 February), this month is dedicated to the resources which are hosted in the CLARIN:EL Infrastructure and constitute members of the Greek Corpora Resource Family.

Dionysis Goutsos, Professor of Text Linguistics at tge School of Philosophyof the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, talks about the Diachronic corpus of Greek of the 20th century.

"The Diachronic corpus of Greek of the 20th century includes language data from the first nine decades of the twentieth century (1900-1989). (For the decades 1990-2010, the Corpus of Greek Texts is available). It was funded in the frame of the action ARISTEIA (Excellence) by the European Cohesion Fund and the Greek government (General Secretariat for Research and Technology).

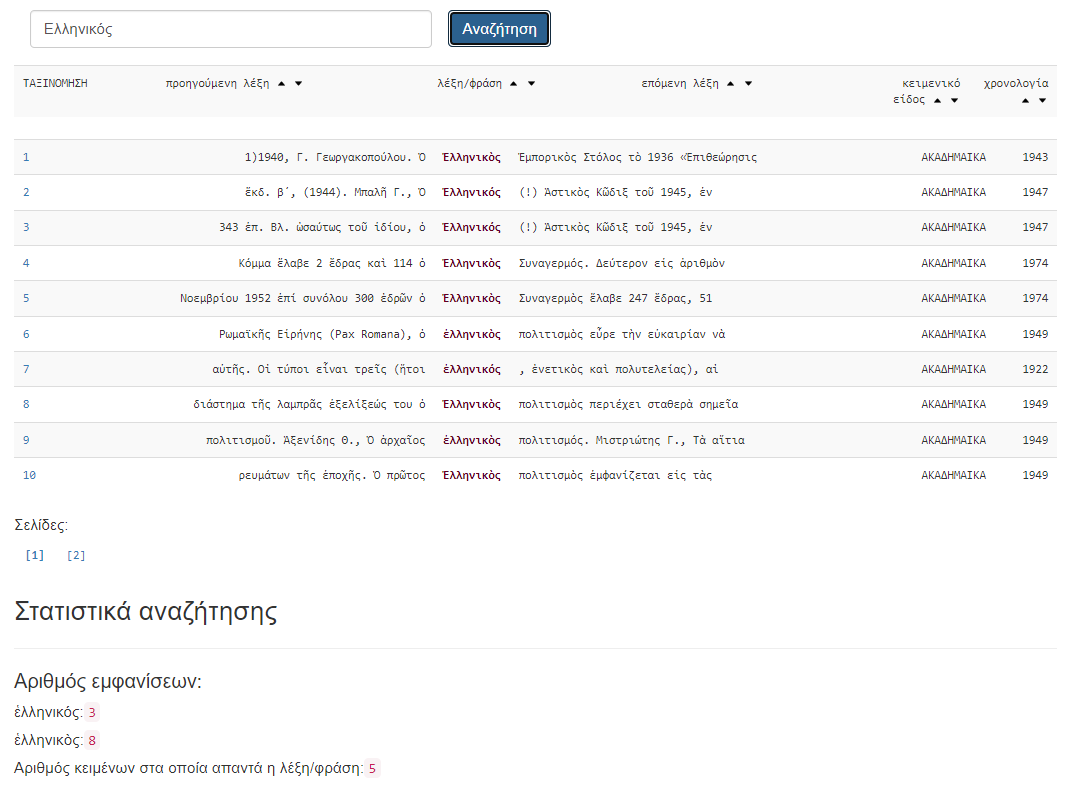

The corpus includes about 3,000 texts, totalling approximately 4 million words, from the whole of the nine decades of the 20th century and a variety of textual genres: film news, academic and parliamentary speeches, film dialogues, literature (novels, short stories, poetry, plays, song lyrics, etc.), academic texts from various scientific fields, legislative and administrative texts, private letters, etc. In the official website of the corpus, users can be provided with access to the fully processed data (mainly academic texts), with more texts being constantly added.

The systematic study of language is now based on large collections of language material that allow researchers to examine a significant amount of data so that useful generalizations about the language, but also about other phenomena, e.g. cultural phenomena of the period that is being examined, can be made in a relatively safe way. Text corpora allow us to extract information about language from data that are:

- empirical: not based on conjecture or linguistic intuition, but on the reality of communicative interactions through language

- systematic: they have been collected on the basis of specific criteria and principles, and not in a random or fragmentary way

- authentic: they are not derived from experimental or other artificial conditions, but from the spontaneous natural speech production of the speakers of a language

- textual: comprising whole texts or parts of texts and not limited to single words or sentences

- extensive: they are large in volume and are not limited to a few examples.

Text corpora are now used in various applications from lexicography to digital humanities studies, as well as in the development of language teaching materials, in the study of student writing, in teaching practice, etc., but also they are used by ordinary speakers of a language who are curious to explore more about their language. For example, teachers can use text corpora to search for authentic materials for teaching a language element or in order to check ready-made teaching materials.

While in the 1990s the first cutting edge synchronic text corpora in English appear (FLOB and Frown), it is in this decade as well that the two major synchronic text corpora in Greek appear, namely the Hellenic National Corpus (HNC) and the Corpus of Greek Texts (CGT). Since then, specialised collections of texts such as the Portal for the Greek Language or the Corpus of Spoken Greek of the Institute of Modern Greek Studies have been developed, as well as diachronic collections of mainly literary texts such as the Cultural Thesaurus of the Greek Language (1774-2000) or the Study of Modern Hellenism, etc. In contrast to other languages, however, such as English for which the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA), the LOB and the British National Corpus (BNC) were created, for the Greek language no large diachronic text corpora have been developed, even though it is a language with such a long written and oral history.

The first research efforts in the Diachronic corpus of Greek of the 20th century offer valuable data for an overview of the history of our language. For example, they show that the idea of contrast between katharevousa and demotic is rather simplistic and that we have to distinguish between conservative, on the one hand, and innovative, on the other hand, textual genres (e.g. academic texts and literature, respectively), which are placed at one of the two poles of social bilingualism, and textual genres that either show little variety (film dialogue) on the one hand, or show a wide range of variety (letters) on the other. Therefore, we cannot talk about an absolute dichotomy of katharevousa and demotic in the linguistic practices of speakers, as we can see in their perceptions of language. However, much remains to be studied: the emergence and prevalence of new greek words ("στοχεύω" versus "σκοπεύω"), or conversely the disappearance of older forms ("διά"), as well as various changes in linguistic means of evaluation, how "έκτακτα" or "περίφημα" give way to "υπέροχα" and "τέλεια", or how the transition from classical culture to classical phobia is being made.

Finally, the picture of the fascinating history of our language will remain incomplete as long as we do not go further back, for example to the 19th and 18th centuries -why not to the 17th and 16th centuries as well?- and do not link the great historical phases of Greek (ancient Greek, medieval Greek, common modern Greek) to each other with a "megasoma" of texts that will shed light on the long oral and written history of our language."

Dionysis Goutsos

Professor of Text Linguistics, School of Philosophy, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

Resource information

Greek

Preview

Me, my family & other resources initiative is based on the CLARIN Resource Families initiative, in which the CLARIN:EL Infrastructure is actively involved having contributed so far a large number of resources for all the Resource Families of the CLARIN ERIC European Infrastructure.